Oysters are like the superheroes of our sea – small, shelled wonders that work miracles for our planet. You might think of them just as fancy, delicious seafood that you have ever so often for dinner, but, in fact, these filter-feeders play a vital role in keeping oceans healthy and clean.

—

Filter feeders are animals that eat by straining tiny particles – like plankton, algae, and even pollution – right out of the water. Oysters are amazing at this; they open their shells, pump water across their gills, and trap food (and junk) on a layer of mucus. Then, they either eat it or bundle the leftovers into “pseudofeces” and spit it out. One grown-up oyster can clean up to 50 gallons (almost 200 litres) of water every single day.

Now, let’s see some examples of what happens when oysters disappear – and what happens when we bring them back.

In the 1800s, Chesapeake Bay in the United States was an oyster paradise with billions of these molluscs filtering the water. But by the early 2000s, 99% of them were wiped out from overfishing, pollution, and disease.

According to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, “in the late nineteenth century, the Bay’s oysters could filter a volume of water equal to that of the entire Bay in three or four days; today’s population takes nearly a year to filter this same amount.” This alarming statistic calls attention to how much humans can damage an ecosystem. How did we get to this point?

Well, another part of the story is what happened on land: over the last century, forests gave way to cities, suburbs, and farms. Rain now washes huge amounts of nutrients (like nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers) and sediment straight into rivers and the Bay; the excess nutrients act as catalysts for algae blooms that suck oxygen out of the water and create “dead zones” where baby oysters cannot survive. On top of that, the muddy sediment smothers adult oysters and blocks the sunlight that underwater grasses need to grow.

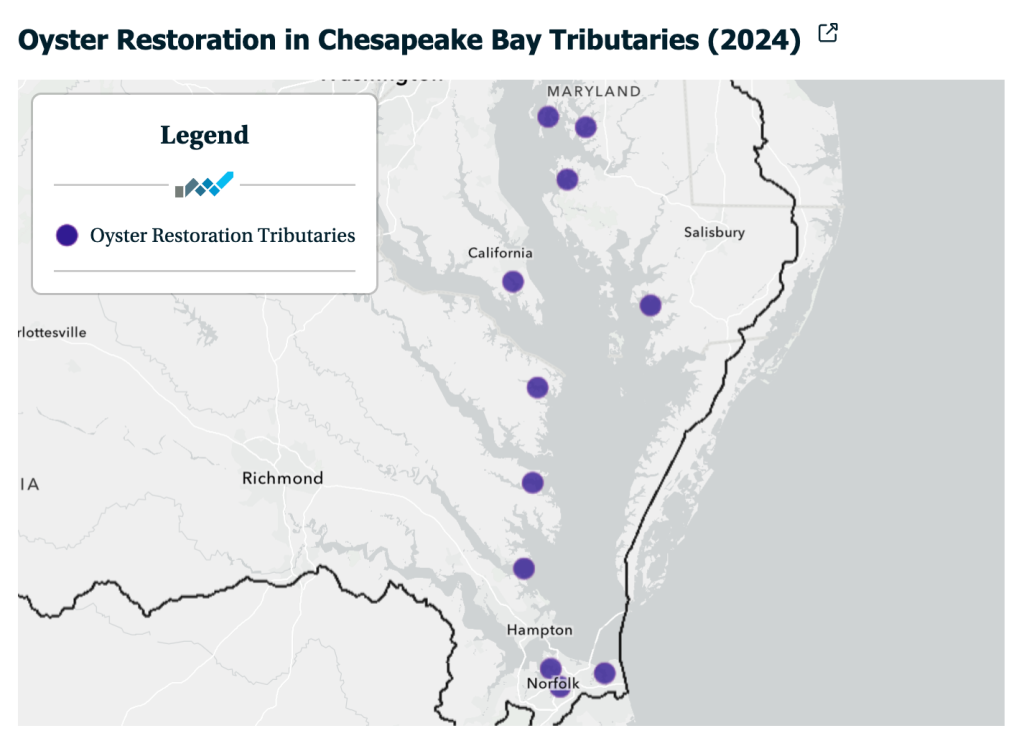

Recognizing this disaster, scientists, volunteers, and local partners – including the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and the US Army Corps of Engineers – launched ambitious restoration projects across key tributaries.

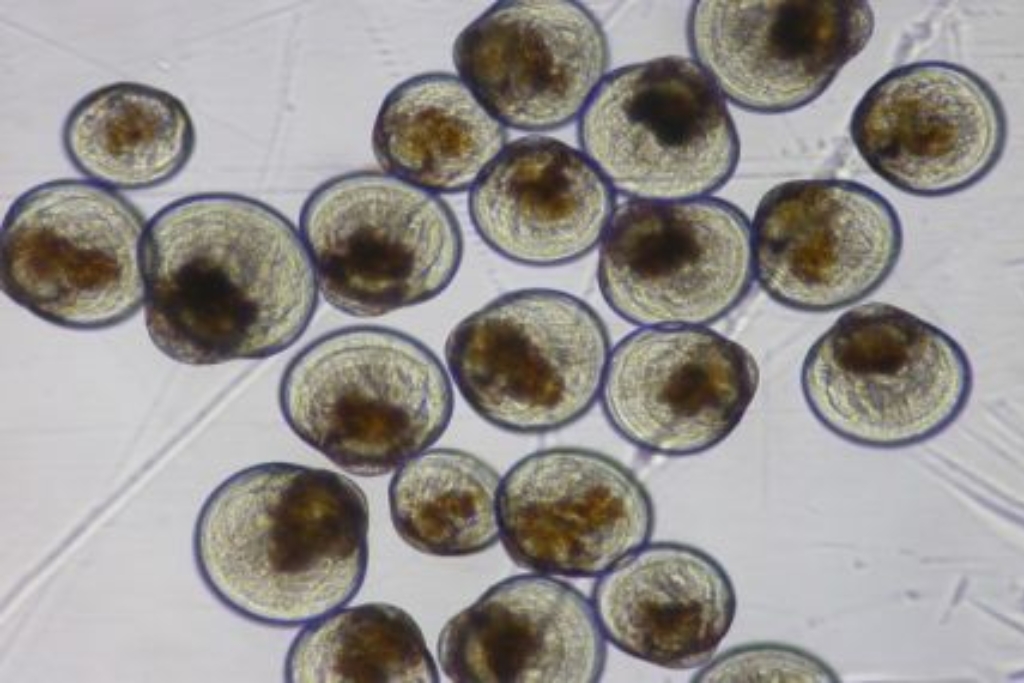

They built reefs using stone substrates, oyster castles (clever concrete-and-shell structures), and recycled materials, then seeded them with millions of hatchery-raised baby oysters or spat-on-shell.

The turnaround has been staggering. In places like Harris Creek and the Little Choptank River, restored reefs have hit success targets for density and biomass; in other locations like Manokin and Lower York, reconstructed reefs have exceeded these targets – with multiple generations of oysters now thriving and accumulating protective shell layers.

These reefs filter pollutants to sharpen water clarity, revive seagrass beds by letting sunlight through, and support the fish and crab populations that call Chesapeake Bay home. Beyond that, the craggy reefs form bustling 3D habitats for hundreds of species, while the oysters themselves absorb carbon dioxide to craft their shells, mitigating the otherwise drastic impacts of ocean acidification.

With nearly $115 million invested and over 2,000 acres of reefs revived so far, these efforts have the Bay filtering water faster than before, paving the way for stronger ecosystems and recognition of the importance of oysters.

Still not convinced? Let’s head to the other side of the planet.

In the 1990s, Australia’s Sydney rock oysters nearly vanished due to overharvesting and the seasonal outbreaks of QX disease. As a result, rivers like the Hawkesbury, Georges, and Derwent Rivers filled with muddy runoff and dead zones where almost nothing could survive. In a bid to stop this, the New South Wales government stepped in, instating an oyster breeding program designed to promote faster growth and increase disease resistance.

Today, these efforts have successfully boosted survival rates for a spat (a baby oyster that has attached itself to a surface) exposed to QX disease up to 80%, and resulted in selectively bred oysters growing up to 25% faster than wild Sydney rock oysters – talk about goals being achieved!

Breeding run of the Sydney Rock Oyster Breeding Program, taking place from October to December (photos: NSW Government)

Nursery run of the Sydney Rock Oyster Breeding Program, taking place from January to July (photos: Sydney Rock Oyster Breeding Program)

Growout and next breeding run of the Sydney Rock Oyster Breeding Program, taking place from January to July (photos: Sydney Rock Oyster Breeding Program)

Here’s something very important to understand: oysters are amazing filters, but they do not magically neutralize dangerous toxins like heavy metals, pesticides, or harmful algal bloom poisons. Instead, these contaminants build up inside their bodies (a process called bioaccumulation). That’s exactly why oyster restoration only reaches its full potential when we also keep our rivers and bays clean. Healthy oysters and protected waters go hand-in-hand – one cannot do the job without the other.

Oysters are the constant, reliable, beating heart of coastal ecosystems. When we give them clean water and safe places to grow, they reward us with clearer seas, stronger shores, and thriving wildlife.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons.